It's estimated there are 7.9 million people in the UK without the Foundation Level of skills needed to use the internet and associated devices by themselves, accounting for 15% of adults in the UK.

These skills include being able to open a browser; using a mouse and keyboard; entering login details; manage passwords; setup a WiFi connection; and adjust device settings.

Digital exclusion is most often a problem for older people, those living alone, people with lower levels of education, and those with impairments, as well as people on low incomes who lack the financial power to get online.

What is digital exclusion?

Official measurements of digital exclusion in the UK include anyone who has never used the internet or has not used it within the last three months.

That's according to the Office for National Statistics (ONS) who monitor digital exclusion and regularly publish reports showing how things are improving.

They point to the Government's Essential Digital Skills Framework which cites six areas people need to be confident in to be classed as digitally included

- Foundation skills such as turning on devices and understanding the concept of accessing the internet

- Communication skills such as communicating security, using word processing software to create documents and using social media platforms

- Handling information and content skills such as understanding not all information online is reliable, using search engines and organising content on their device

- Transacting skills such as setting up accounts online, accessing public services online and managing transactions securely

- Problem solving skills such as using the internet to find information and using live chat or tutorial facilities to solve issues

- Skills to stay safe and behave legally online such as setting privacy settings, recognising suspicious emails and understanding intellectual property rights

Mastering skills within these categories moves a person from digitally excluded to digitally included, but it's worth looking at why people are digitally excluded in the first place.

What contributes to digital exclusion?

Four main factors contribute to digital exclusions:

- Access: both physical and financial

- Motivation: including understanding or appreciation of the benefits

- Skills: including whether they have any available means of learning ICT skills

- Confidence: including fears of fraud and online security

Let's look more closely at these factors.

Lack of access

The older and more financially disadvantaged we are, the less likely we are to have quick and easy access to the internet.

Ofcom's Communications Affordability Tracker, last published December 2024, found:

- 25% of UK households struggled to afford their communications service

- 8% of UK households struggled to afford their fixed-line broadband plan

Meanwhile, The UK Consumer Digital Index 2024 report by Lloyds Bank, also found:

- 3% of people who weren't online thought it was too expensive

Affordability is known to be one of the main drivers of digital exclusion, with people needing to have access to both mobile and broadband at home, with public services much less secure.

Despite the existence of social broadband tariffs like BT Home Essentials, nearly 69% of eligible households are still unaware of these tariffs. In addition, there are also equipment costs stopping people getting online, with limited resources to access cheap refurbished computers and tablets.

Lack of motivation

Many people who aren't already online say they don't understand the need for digital engagement.

Of those not connected, Lloyds found:

- 26% said they were just not interested

However, despite this, Lloyds' research found those with the highest digital capability were:

- Saving nearly four times more often

- Saving almost three times as much

- Almost 1.5 times more likely to have more money in their pockets through shopping around more often

Other benefits to being online include access to NHS and banking apps, as well as improved access to council, housing association and benefit services.

The barrier of encouraging people they would benefit from being online is one we cover more deeply in our guide to getting other people online.

Lack of skills and confidence

We've combined these two factors because they're two sides of the same coin: many people lack the skills, but they also lack the confidence to obtain the skills.

Findings from Lloyds show:

- 16% thought the Internet was too complicated

- 23% have very low levels of digital capability

- A further 9% have low levels of digital capability

However, as many as 77% of UK adults said they would welcome help to become more financially confident, including being able to access online budgeting tools.

Compared with the highest levels of digital capability, those with the lowest capability were also:

- Less confident online (60% vs 94%)

- Less likely to engage with their finances digitally (6.7% vs 100%)

- More likely to be scammed multiple times (8.5% vs 4.6%)

Previously research by Lloyds in 2020 asked consumers what would persuade them to get online, with five ideas suggested to encourage them:

- The ability to easily stop organisation from using their data (25%)

- Getting support from someone to help such as friends or family (24%)

- More transparency about the data organisations have on them and how they're using it (24%)

- Cheaper cost of devices (23%)

- If websites or apps were easier to understand (22%)

The first and third points here raise some additional questions about privacy and the lack of confidence people have in organisations who use their data as much as the lack of confidence they feel in getting online.

For younger people who have grown up with a digital footprint, these concerns may seem alien, but they're representative of debates going on in governments and courts across the world.

Those who have never been online ask why they would want to risk their personal information by potentially giving it to organisations who don't take care of it.

Whether this is a real risk or one that's exaggerated by high profile data leaks like the 2018 Ticketmaster scandal, it's still an important barrier to address.

Read more about protecting personal data online.

Who is digitally excluded?

The barriers discussed above affect different people to different degrees, with the result that some groups are much more likely to be digital excluded.

Older people

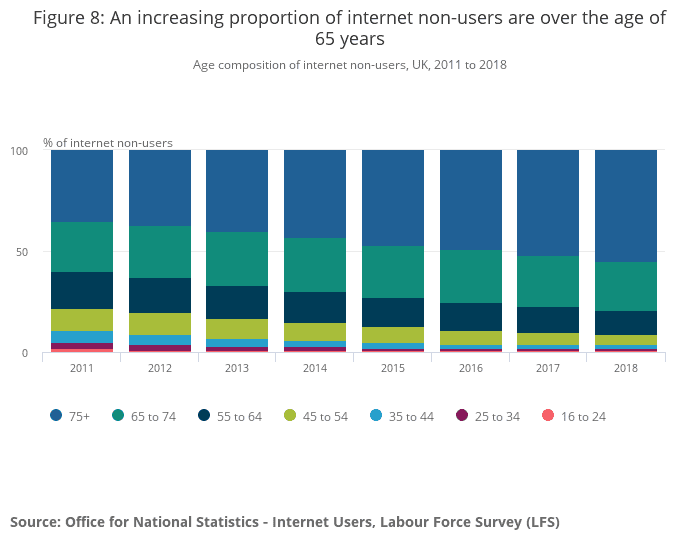

ONS figures show the over 65s make up an increasingly high proportion of internet non-users.

In their latest research, covering the period January to March 2020, the chance of an internet non-user being aged 85 and over was highest, at 315.59, while being 75 to 84 the chance was 146.91.

When we compare this to other age brackets it's clear how high the likelihood of being older affects the chances of also being an internet non-user. For example, the chance of a non-user being aged 16 to 24 is just 0.85, while the chance of being aged 35 to 44 is just 1.52.

Looking at older data over time, we can also see how the percentage of older users has increased since 2011, with the numbers of non-users in age brackets below 65 has decreased.

As the graph above shows, 79% of non-users in 2018 were 65 or over, with 55% over the age of 75. This compared to 25% and 36% respectively back in 2011.

So, while younger and middle-aged people have improved their digital inclusion during those seven years, the skills gap for the over 65s remains clear and stark.

This data is backed by Lloyds who say age is still the dominant driver of digital capability, with almost nine in ten of those in the Very Low digital capability segment aged over 50.

Read more about why older people should be getting online.

People with disabilities

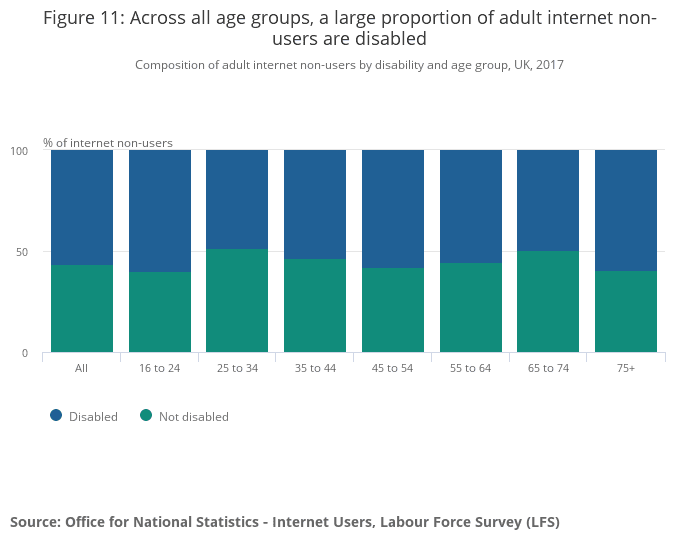

Disabled adults make up a large proportion of non-users of the internet according to ONS figures from 2017. This covers all age groups as the graphic below shows:

More recent data from 2020, also backs this up, with the odds ratio of being disabled and a non-internet user standing at 5.19.

Disability is a key reason younger people don't access the internet, with 60% of the digitally excluded between the ages of 16 and 24 classing themselves as disabled.

The positive news is the percentage of disabled adults not using the internet is declining. In 2014, it was almost 35% but this was down to just over 23% by 2018.

Separately, previous Lloyds' research from 2021, asked those with an impairment which technologies they used to help them digitally. These were the results for those with high or very high levels of digital engagement:

- 55% used biometric recognition tools like face identification or fingerprint recognition

- 44% used voice assistants

- 8% used technology to help with mobile impairments

- 4% used screen readers

The figures for those with very low or low digital engagement were much lower, suggesting there are opportunities for disabled adults to improve their digital engagement through tools like screen readers and dexterity supports.

One major problem here is the financial implications of all this: extra accommodations cost money that many disabled people simply don't have to spare.

While there are charities and organisations able to help, many people either don't want to ask for the support or think it isn't for them.

Financially disadvantaged people

More widely, financial disadvantage is a key reason why people don't use the internet.

Lloyds research from 2024 highlighted how the profile of those less likely to engage digitally was people earning less than £35,000 per year.

41% of those in the Very Low digital capability segment also earned less than £20,000 per year. This compares to just 13% earning under £20,000 in the Very High digital capability segment.

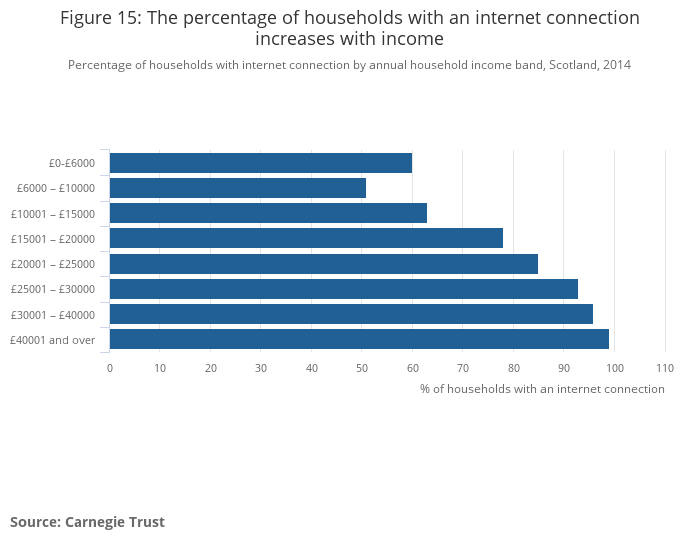

We've seen from Ofcom's latest research, how 25% of households in the UK are already struggling to afford their communications service, and previous figures from the Carnegie Trust on the correlation between low household income and the lack of a household internet connection in Scotland back that up:

There are some tangible reasons why someone may feel they can't afford to be online:

- Cost of the equipment to get online

- Cost of the broadband connection

- Inability to pass credit checks

At the time of writing, the cheapest standard broadband plan costs from £23 per month, while social tariffs usually cost around £15 per month. For households in poverty, this might well be unaffordable, especially for a service they don't think they need.

The unfortunate irony of digital exclusion is that it often leads to financial exclusion, meaning customers can pay more for services because they're not online. For example:

- They may miss out on cheaper energy tariffs which are often online only

- Managing accounts online is often cheaper

- As physical bank branches close, banking online is cheaper than travelling to another branch possibly miles away

There are also issues with services being digital by default, so councils expect residents to fill in forms online and Universal Credit applicants are meant to apply online wherever possible.

So, those on tight budgets are stuck in the unfortunate situation of needing to pay more for services because they're not online but being potentially unable to get online even if they wanted to due to financial constraints.

Summary: how can we solve digital exclusion?

Digital exclusion is a multifaceted problem affected by issues including age, disability, skills, money motivation and confidence.

It's clearly something that isn't going to be solved by one policy or one concerted push to talk to those who are uninterested in getting online.

The Carnegie Trust recommends a 12-step approach for Governments and organisations to take:

- Commit to digital inclusion strategies

- Prioritise co-production of strategies with those who have experienced digital exclusion

- Collect quality digital data

- Establish a robust baseline for a Minimum Digital Living Standard

- Embed digital inclusion across public services

- Align with anti-poverty efforts to show digital inclusion could help

- Measure the impacts of programmes supporting digital inclusion

- Regulate for online harms to promote a safer online environment

- Invest and build capacity to support organisations trying to help digital inclusion

- Champion the role of business to promote digital inclusion

- Innovate for inclusion for those on low incomes

- Ensure a public safety net to provide internet access such as libraries, health and welfare services, and community groups

Overall, these policies would go some way to overcoming many of the barriers preventing digital inclusion, but whether they would be enough to combat that 26% who say they have no interest in going online is still up for debate.

One final piece of good news though: Lloyds research also found the number of people digitally disengaged has steadily decreased over recent years. An additional 3.9 million people are now using the internet in 2024 compared to 2016, with just 3% (1.6 million) people remaining offline.

Read our guides to staying safe while browsing online and staying safe when communicating via email.